May 1, 2025

In a media-saturated world, disinformation doesn’t just spread—it evolves. It shapeshifts, mutates, and embeds itself in our cultural and emotional DNA. And more often than not, it does this visually.

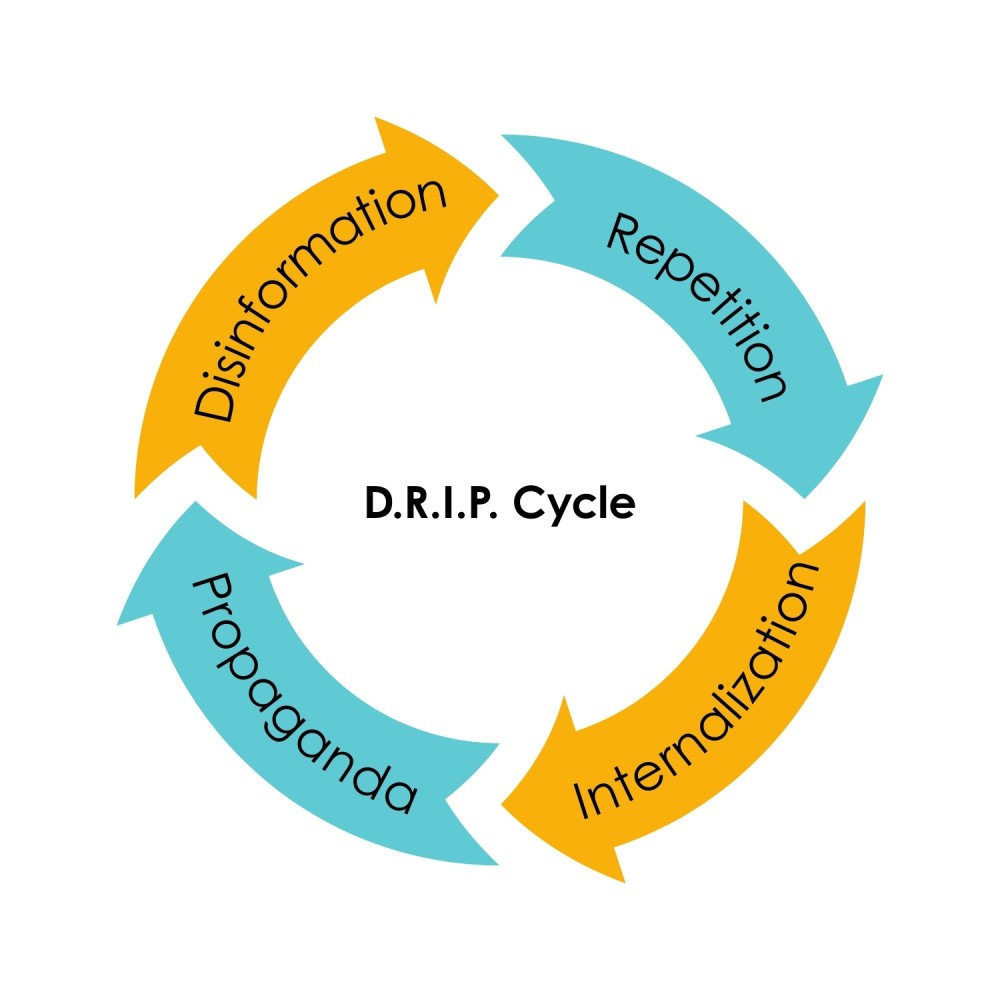

I’ve been reflecting on this a lot lately, especially as an artist, cultural strategist, and someone deeply concerned with how we understand power. So I developed a new framework to make sense of what I’m seeing—not just in politics, but in our everyday feeds. I call it the D.R.I.P. Cycle:

Disinformation → Repetition → Internalization → Propaganda

What does that mean?

It means that lies don’t become powerful all at once.

They drip. Slowly. Repeatedly. Visually. Until they become the foundation of a new belief system.

And nothing accelerates that process faster than visual propaganda.

Let’s break it down:

1. Disinformation (The Spark)

It starts with a post, a meme, or a TikTok: a headline that feels true, even if it’s not. Propagandists know the secret sauce is emotion. So they lean on fear, outrage, nostalgia. The image does the heavy lifting—think children crying, burning flags, bold warnings like “They’re coming for your rights.” These visuals bypass logic. They hit you in the gut.

Propagandists initiate the cycle by creating emotionally charged, misleading visuals designed to provoke immediate reactions.

AI-Generated Misleading Images: Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini’s far-right League party disseminated AI-generated images depicting men of color as violent criminals. These images, presented as news, were intended to incite fear and xenophobia.

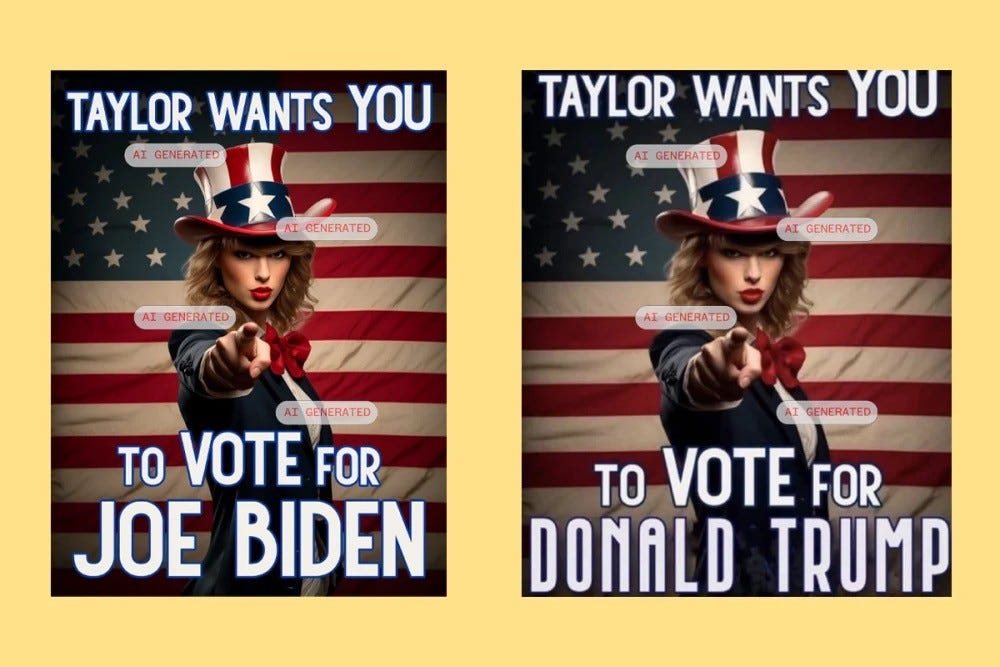

Fabricated Endorsements: Former President Donald Trump shared AI-generated images falsely showing Taylor Swift endorsing his campaign, aiming to sway public perception through fabricated celebrity support.

2. Repetition (The Flood)

Then, like a catchy song stuck in your head, it repeats.

The same idea—“the system is rigged,” “they’re lying to you”—circulates in different colors, languages, formats. Memes, reels, infographics. It’s algorithmic propaganda: visual content designed to flood your screen until the disinformation starts to feel like common knowledge.

Once disinformation is introduced, it is rapidly disseminated across various platforms, reinforcing the false narratives.

China’s “Never Kneel” Campaign: In response to U.S. tariffs, China launched a propaganda campaign utilizing Cold War-era imagery and AI-generated memes, portraying the U.S. as a bully and emphasizing China’s resilience. The campaign was widely shared on platforms like Douyin and WeChat.

“Children of War” Campaign: A Russia-linked propaganda effort aimed to erode German support for Ukraine by circulating emotive imagery of children purportedly killed in the conflict, thereby manipulating public sentiment through repeated exposure.

3. Internalization (The Shift)

This is where it gets deep. The viewer becomes the believer. They start creating their own visuals, echoing the same points, often with emotional backstory: “I used to trust the system… until I saw this.” Visuals become self-made proof. Identity begins to harden around the aesthetic of the ideology.

As individuals are repeatedly exposed to these visuals, they begin to internalize the messages, adopting them as personal beliefs.

“Womanosphere” Movement: Conservative media outlets and influencers promote traditional gender roles through aesthetically pleasing content, leading young women to internalize regressive ideals under the guise of empowerment.

4. Propaganda (The Doctrine)

Now it’s no longer about belief—it’s about conversion.

Visual propaganda becomes cinematic, strategic, persuasive. It’s used to recruit, to brand, to divide. The goal isn’t just to spread ideas anymore—it’s to build us vs. them. The visual language turns into doctrine.

The internalized beliefs are then transformed into widely accepted doctrines, further propagated through sophisticated visual campaigns.

“Trump Gaza” Video: An AI-generated video shared by Donald Trump depicted a utopian vision of Gaza under his leadership. Originally intended as satire, the video was presented without context, serving as a propaganda tool to promote his policies.

Why does this matter?

Because visuals don’t just carry messages—they shape memory, emotion, and identity.

And as artists, designers, media makers, and cultural workers, we’re either helping people see clearly… or letting them drown in the drip.

Understanding the D.R.I.P. Cycle helps us:

Recognize the stages of belief manipulation

Disrupt the normalization of falsehoods through design

Create more intentional, truth-based media that speaks to emotional and cultural realities

We can’t fight propaganda with bullet points. We need counter-narratives that are just as emotionally resonant—but rooted in care, clarity, and accountability.

Let’s resist the flood—one image at a time.

Denise Zubizarreta is a Ph.D. student in Applied Social Justice at Dominican University, with an M.A. in Arts Leadership and Cultural Management from Colorado State University and a B.F.A. in Fine Art from Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design. She is the creator of the Colonial Stockholm Syndrome (CSS) framework, which she explores in her forthcoming book examining the psychological grip of colonialism on identity, belonging, and political behavior.

She serves as the Director of Development and Communications for the New Mexico Local News Fund and the Engagement and Development Director at Latina Media Co, where she advocates for equitable media ecosystems and the amplification of Latiné voices in journalism and cultural criticism.

As a scholar, cultural operations strategist, and interdisciplinary artist of Puerto Rican and Cuban descent, Denise focuses on colonization’s emotional and systemic legacies within diasporic and immigrant communities. Her research and artwork critically examine how disinformation is used as a tool of control, shaping public perception of immigrants, eroding trust, and reinforcing colonial narratives. Through her work, she bridges academic inquiry and lived experience to expose the roots and repercussions of propaganda in today’s polarized media landscape.