If you’re new here, welcome.

The Colonial Condition is more than a publication — it’s a practice in unlearning. It’s where I unpack how colonial psychology continues to shape our politics, media, and daily lives, and where I introduce the frameworks I’ve been developing over the last decade to help us name what we feel, see, and internalize.

This article serves as your orientation — a grounding in the foundational theories that run through my work. If you’re just getting situated, this is a good place to start.

Colonial Stockholm Syndrome (CSS)

When love and loyalty become survival mechanisms.

At the heart of my research is Colonial Stockholm Syndrome (CSS) — the psychological condition in which colonized or formerly colonized people develop a sense of emotional dependency, loyalty, or admiration for their colonizers and the systems they represent.

This isn’t about ignorance or weakness. It’s about survival.

“Colonialism didn’t just conquer land — it colonized intimacy.”

Under colonial rule, aligning with power was often the only path to safety. Accepting the colonizer’s language, religion, or cultural codes could mean access to food, education, or employment. It could mean staying alive. Over generations, this survival strategy hardened into something deeper — a learned emotional reflex, a love laced with fear.

CSS reveals how violence, when sustained over time, disguises itself as care. The colonizer becomes both abuser and savior, offering protection from the very harm they create. The colonized, meanwhile, learns to express gratitude for the smallest gestures of mercy.

Like all trauma bonds, CSS depends on repetition — on the cyclical breaking and mending of trust.

Each act of domination is followed by a performance of “benevolence”: a new school, a paved road, a flag raised in the name of progress. The colonized psyche learns to interpret these as gifts rather than the instruments of control they are.

“Empire teaches its captives to confuse dependency with devotion.”

CSS mirrors the structure of an abusive relationship:

The colonizer plays both oppressor and provider, maintaining control through manufactured dependency.

The colonized reinterprets harm as benevolence — a coping mechanism turned cultural inheritance.

Gratitude becomes a survival currency, traded for dignity and autonomy.

This emotional conditioning explains why, centuries later, remnants of affection for the colonizer still surface in collective memory and national discourse. When people say “we were civilized,” or “things were better under (colonial rule),” they are not expressing nostalgia for oppression — they are echoing the voice of a survival mechanism that has not yet been deactivated.

CSS is a form of psychological captivity where love becomes the tool of control. It is the emotional residue of oppression — the way a people learn to romanticize their own subjugation because the alternative (grief, rage, rupture) feels too dangerous to bear.

Generational Inheritance and Cultural Continuity

CSS is not an event; it is a transgenerational pattern. Colonization doesn’t simply end when the empire withdraws — it continues through the inherited beliefs, rituals, and relationships that define identity.

In families, CSS can manifest as reverence for whiteness, preference for European ancestry, or shame toward Indigenous and African roots. It shapes parenting, religion, education, and even romance. Children grow up absorbing the subtle lesson that proximity to the colonizer — whether through language, aesthetics, or behavior — ensures safety and worth.

“Colonial Stockholm Syndrome is not only about who we love; it’s about who we are allowed to be loved by.”

In communities, CSS shows up as political loyalty to oppressive systems, the idolization of foreign authority, or the insistence that progress must come from the same empire that once destroyed us. It’s the cognitive dissonance of people who wave the colonizer’s flag at independence parades, who defend imperial wars in the name of democracy, or who equate assimilation with success.

The Modern Face of CSS

CSS is not confined to history. It persists in contemporary politics, economies, and aesthetics.

For example, in the Caribbean, tourism economies reconstruct the plantation hierarchy as spectacle: locals serving, smiling, performing paradise for foreign consumption.

In the diaspora, nostalgia for empire appears in the craving for European validation — through education, art institutions, and cultural capital that still gatekeeps access to legitimacy.

“Empire doesn’t need to rule you to own your desire.”

CSS operates wherever colonized people measure their worth through the colonizer’s approval — when English feels like intelligence, when lightness feels like beauty, when distance from one’s roots feels like arrival.

And yet, within CSS lies a paradox. The very empathy and adaptability that allowed colonized people to survive are also the qualities that make liberation possible. The same emotional intelligence that once kept us safe can now become the tool of awakening — if we learn to redirect it inward, toward ourselves and our own histories.

“CSS is the colonial condition of the heart — the emotional logic that keeps us loving what breaks us, and the first truth we must unlearn to heal.”

The Colonial Psychological Complex (CPC)

The architecture of the colonial mind.

If Colonial Stockholm Syndrome (CSS) reveals the emotional pattern of attachment under domination, the Colonial Psychological Complex (CPC) exposes the internal structure that keeps that attachment alive.

The CPC is not a single symptom — it is an entire psychological architecture, a multi-layered internal system designed to maintain the illusion of the colonizer’s authority and the colonized person’s dependency. It is the emotional scaffolding that holds the empire upright long after its walls have fallen.

“Colonialism built nations, but it also built a mind — and that mind keeps rebuilding empire in its own image.”

The CPC functions as the psychic infrastructure of colonization — the invisible operating system through which inherited hierarchies of power, race, gender, and faith are normalized. It lives in our cultural rituals, our institutions, and our inner conversations about worth, belonging, and identity.

The Anatomy of the Complex

The CPC is made up of four interlocking dynamics — each one reinforcing the others like gears in a machine.

Colonial Narcissism Syndrome (CNS)

The colonizer’s psychological core — a grandiose self-image rooted in moral and intellectual superiority.

CNS frames domination as destiny. It allows those in power to see themselves not as exploiters but as civilizers. It’s the mindset that turned plunder into “progress” and oppression into “order.”

“CNS is the empire’s mirror — polished to reflect only its own benevolence.”

Colonial Savior Complex (CSC)

The emotional companion to narcissism. CSC is how colonizers rationalize their control: by casting themselves as rescuers. It’s the missionary impulse, the development project, the humanitarian campaign — all rooted in the belief that salvation must come from the top down.

CSC sustains modern versions of empire through “aid,” “democracy promotion,” and “philanthropy” that reproduce dependency rather than autonomy.

Colonial Stockholm Syndrome (CSS)

The colonized person’s adaptive response. CSS is the emotional glue within the complex — the learned affection that stabilizes oppression. Through it, domination becomes mutual performance: the colonizer needs to be admired; the colonized needs to be accepted.

Colonial Social Conditioning (COSOC)

The systemic reinforcement that keeps the entire structure intact. COSOC operates through schools, media, religion, and family. It shapes what we define as intelligent, beautiful, or civilized. It rewards conformity to colonial aesthetics and punishes deviation from them.

Together, these dynamics form a closed circuit of power — a psychological feedback loop that operates even without direct force.

“The CPC doesn’t need an emperor; it only needs believers.”

The Function of the Complex

The CPC works by creating mirrors of hierarchy — convincing the colonizer and the colonized that their respective positions are natural, deserved, and divinely ordered.

For the colonizer, the complex grants moral innocence: the ability to dominate without guilt.

For the colonized, it generates learned dependency: the feeling that liberation would be chaos, that freedom must be mediated by the master’s guidance.

It’s a psychological choreography of consent — the colonized internalize the colonizer’s values until resistance feels like betrayal.

This is why liberation movements often fracture from within. The CPC ensures that even revolutionary spaces can reproduce colonial hierarchies — colorism in independence movements, patriarchy in anti-imperial struggles, elitism in decolonial academia. The architecture of empire survives by rebuilding itself inside its challengers.

“The CPC is the empire’s favorite trick — to make rebellion speak its language.”

The Emotional Landscape of the CPC

The CPC doesn’t operate only through ideology; it operates through feeling.

It’s the inherited guilt of the colonizer, the internalized shame of the colonized, and the collective amnesia that binds them together.

For the colonizer, it produces denial and dissonance — the inability to face the brutality of their history without fracturing the myth of moral superiority.

For the colonized, it produces fragmentation — a split between pride and self-rejection, love and resentment, belonging and exile.

For society, it manifests as collective nostalgia — a longing for “the order” of colonial times, a yearning for a world that never truly existed.

CPC ensures that both sides remain emotionally invested in the relationship — one through guilt, the other through gratitude. The result is a shared dependency built on trauma.

“The colonizer cannot release control, and the colonized cannot yet trust freedom.”

The CPC and Modern Power

The Colonial Psychological Complex didn’t disappear with independence; it adapted to new regimes of control.

Today, it animates everything from global capitalism to cultural representation.

In economics, it manifests as debt colonialism and dependency on foreign investment.

In education, curricula are centered on Western thought as the universal truth.

In media, as storytelling that privileges whiteness as neutral and casts the Global South as peripheral or primitive.

In technology, as algorithmic bias — machines trained on colonial data sets that replicate the same hierarchies in code.

The CPC evolves because it no longer needs colonial flags to function. It thrives in language, in aspiration, in aesthetics. It governs how we imagine progress and whose progress is worth celebrating.

“The CPC doesn’t occupy land anymore; it occupies imagination.”

Unraveling the Complex

To dismantle the CPC, we must first learn to recognize its architecture within ourselves. That means confronting not only the narratives of dominance but also the emotions that sustain them — guilt, shame, fear, admiration.

Decolonization of the mind begins when we ask:

Whose voice am I hearing when I measure my worth?

Who benefits from my compliance?

What parts of myself have mistaken approval for safety?

Unraveling the CPC is not about erasing history; it’s about interrupting inheritance. It’s the process of reclaiming authorship over identity, of remembering that self-definition was always meant to be communal, not conditional.

“The work of decolonizing the mind is architectural — we are not just breaking walls, we are rebuilding foundations.”

Oppressive Cognition

The mind under occupation.

From the Colonial Psychological Complex emerges Oppressive Cognition — the psychological state produced when an individual or community must navigate overlapping systems of domination. It is the cognitive residue of empire: the mental inheritance of those forced to think, act, and survive within multiple structures of inequality at once.

Oppressive Cognition is not just about beliefs — it’s about survival logic. It describes the mental gymnastics required to exist within societies where racism, sexism, ableism, classism, and colonialism intertwine.

For those living under these conditions, the mind becomes a battlefield of negotiations:

How to speak without being labeled angry.

How to succeed without being seen as a threat.

How to claim space without being accused of taking too much.

“Oppressive Cognition is the colonizer’s most enduring invention — a way to make the oppressed self-regulate in the absence of the master.”

When someone experiences multiple forms of oppression, the mind learns to constantly scan for danger — to anticipate bias before it arrives. A Latina woman with a disability, for example, might navigate not only gendered stereotypes and racial bias, but also the ableist assumptions that render her invisible or infantilized. The weight of this compounded awareness produces a constant state of vigilance — a mental hyper-attunement to survival that masquerades as resilience but is, in truth, exhaustion.

Oppressive Cognition lives in that exhaustion. It is the unrelenting labor of managing perception while suppressing authentic emotion. It teaches the colonized and marginalized mind to internalize the hierarchies around it — to equate silence with safety, assimilation with worth, and compliance with belonging.

This manifests daily in quiet, normalized ways:

Professionalism coded as proximity to whiteness — tone, diction, hairstyle, accent, or affect.

Self-policing dressed up as self-discipline — the belief that composure equals credibility.

Ambition entangled with guilt — “If I rise, will I still be accepted by my own?”

Survival gratitude that reframes exploitation as opportunity — “At least they let me in.”

“Oppressive Cognition is not simply thinking under oppression — it is thinking through oppression until it feels like truth.”

For those enduring multiple systems at once — the queer migrant, the Black woman academic, the Indigenous artist with chronic illness — oppression doesn’t arrive as a single force but as a layered ecosystem of expectations. Each system demands a different performance of acceptability, forcing the individual to fracture and shapeshift in order to survive.

This fracturing is what I call the psychic fragmentation of Oppressive Cognition. It’s when the mind divides itself to meet the contradictory demands of oppressive structures — being assertive but not angry, visible but not “too much,” proud but not political. Over time, these internal compromises begin to define one’s sense of self.

Oppressive Cognition also disguises itself as “resilience culture.” We glorify endurance while pathologizing exhaustion. We call it “grit,” “work ethic,” or “professionalism,” when what we’re really describing is the adaptive trauma response of people who were never allowed to rest.

“Oppressive Cognition is the cognitive afterlife of empire — the colonizer’s voice echoing through the descendant’s self-doubt.”

Even in acts of resistance, the mind can become entangled in colonial logic — performing liberation in ways that still seek approval from oppressive systems. It’s the activist who must sound academic to be believed, the artist who softens their truth for funders, the scholar who translates pain into theory because pain alone isn’t considered credible.

Liberation from Oppressive Cognition begins by naming the thought as foreign — by tracing the echo back to its original source. It requires learning to distinguish the voice of survival from the voice of the self.

“To decolonize the mind is not to forget what empire taught us — it is to remember that we were never meant to believe it.”

The D.R.I.P. Cycle

Disinformation → Repetition → Internalization → Propaganda.

The D.R.I.P. Cycle explains how ideology becomes instinct — how falsehoods evolve into feelings, and feelings into unquestioned “truth.”

Disinformation – A false narrative enters circulation.

Repetition – Institutions, media, and cultural traditions echo it until it feels familiar.

Internalization – People absorb it as emotional truth.

Propaganda – That “truth” becomes policy, culture, and behavior.

This is how colonialism transformed brutality into benevolence — how conquest became “civilization,” slavery became “industry,” and cultural erasure became “progress.” But the D.R.I.P. Cycle didn’t end with empire; it simply changed its tools.

“The D.R.I.P. Cycle is not just a process — it’s a psychological rhythm, a slow conditioning of collective memory.”

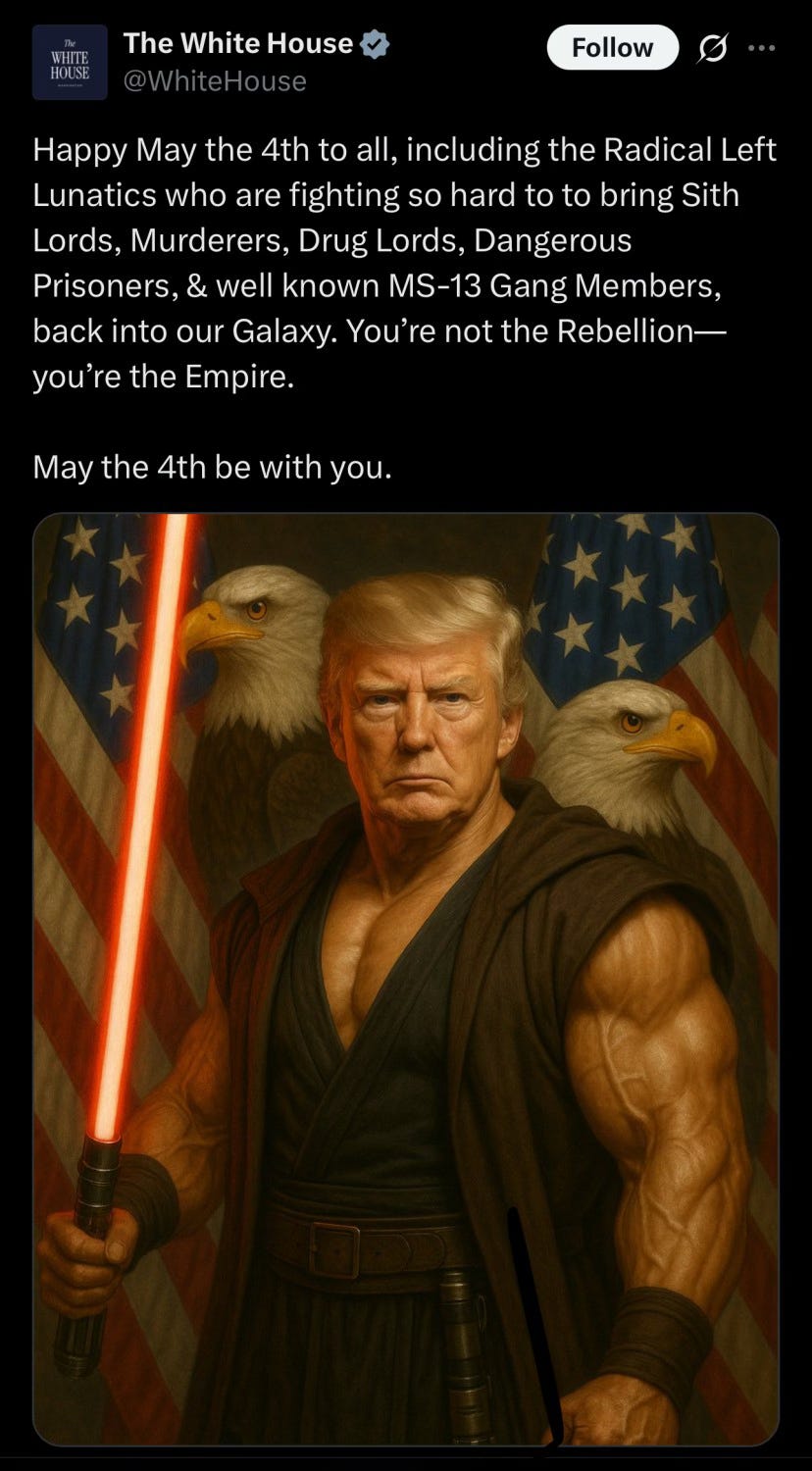

Through the D.R.I.P. Cycle, disinformation operates not only through words but through images. Colonial systems have always relied on visual propaganda — paintings that glorified conquest, photographs that exoticized the colonized body, newsreels that celebrated “discovery.” What has changed is the medium, not the message.

The Visual Turn of Propaganda

In the digital age, propaganda has become visual, instantaneous, and algorithmically amplified.

Memes, films, and AI-generated imagery now act as accelerants in the D.R.I.P. Cycle. Each scroll through a feed is a repetition loop — the more we see, the more we believe.

Images now bypass critical thought and appeal directly to emotion — the most efficient path to internalization. They create what I call aesthetic persuasion — the emotional seduction of an idea before we’ve even had a chance to think about it.

“We no longer need to be told what to believe — we are shown until belief becomes reflex.”

AI has escalated this phenomenon by producing endless variations of the same myth. The colonizer’s gaze can now be automated. With a few prompts, AI can recreate the visual grammar of empire:

Whiteness as purity, beauty, and authority.

Brown and Black bodies as spectacle or danger.

The Global South as ruin or resource.

Femininity as service. Masculinity as dominance.

Each generated image strengthens the repetition phase — flooding the digital sphere with familiar hierarchies disguised as creativity. The result is not just misinformation but aesthetic manipulation — the rebranding of oppression as “style.”

AI-generated propaganda is especially dangerous because it accelerates what the D.R.I.P. Cycle already does best: normalize. In the past, disinformation required time, funding, and print distribution. Now, with a single viral post, falsehood becomes fact in seconds.

And because AI learns from existing colonial data — from centuries of biased archives, photographs, and texts — it doesn’t create something new. It perfects what already existed. It polishes the colonial lens, giving it a modern sheen.

“AI doesn’t invent propaganda — it refines it, training machines on the myths that built empires.”

From Image to Identity

The D.R.I.P. Cycle also connects directly to Colonial Stockholm Syndrome (CSS) and the Colonial Psychological Complex (CPC) by shaping how identity itself is constructed. Visual propaganda teaches us what belonging looks like — who deserves empathy, who embodies authority, who is seen as human.

Repeated exposure to these images embeds them into our subconscious, producing Oppressive Cognition: the belief that these hierarchies are natural. When propaganda reaches this stage of internalization, it no longer needs to convince us — it simply needs to exist.

This is why colonialism was never just a political project; it was an aesthetic one.

Empires didn’t just control borders; they curated the imagination.

Today, that curation is happening again — but instead of canvas or newspaper, it’s happening through algorithmic feeds and AI-generated images that replicate the same colonial logic: domination disguised as innovation.

“In the age of AI, the colonial gaze has gone automated — trained to recreate the same power structures in higher definition.”

The D.R.I.P. Cycle reveals that propaganda is not a singular event but an ecosystem — a feedback loop between imagery, narrative, and emotion. It’s how the same colonial stories keep returning, dressed in new technology.

To interrupt it, we must become conscious not only of what we see but how we are being seen.

The question is no longer what is true, but who profits from your belief?

“Propaganda isn’t only what we’re told — it’s what we come to tell ourselves, and now, what we teach our machines to believe for us.”

Why It Matters

Together, these frameworks form a map of what I call the colonial condition:

a state of psychological captivity where systems of power have learned to live inside us.

Understanding these frameworks allows us to identify how domination hides in affection, how hierarchy disguises itself as harmony, and how liberation begins not just in politics but in perception.

“To unlearn empire is to confront the parts of ourselves that mistake obedience for peace.”

Begin the Unlearning

Every essay here builds from these foundations — some through theory, others through story, history, or art.

If you’ve ever wondered why we defend the systems that harm us, why we confuse power with love, or why the colonial story still feels like home, this space is for you.

If this is your first time reading The Colonial Condition, start with this question:

What beliefs about power, worth, and belonging have I inherited that were never mine to carry?

Every essay here builds on these frameworks — sometimes through theory, sometimes through story, sometimes through art. My goal is to make this knowledge not only accessible but usable — because understanding the colonial condition is the first step toward breaking it.

💭 Subscribe to The Colonial Condition to receive essays, reflections, and frameworks exploring how empire lives inside us — and how we can begin to set it free.